Resistance Training for Youth: An Updated View

I wrote an article two years ago breaking down the latest research regarding resistance training and weightlifting for youth. You can read that article here along with the cited research:

→ Is Weight Training Safe for Youth?

Here’s the quick summary:

· The Sport of Weightlifting and Resistance Training in General are both safe for youth if the program is age appropriate, progressed safely, and monitored by a professional.

· Not only is Weight Training not dangerous for growth plates, lifting weights with appropriate technique creates stronger and thicker bones.

- Compression, or when molecules are pushed together, is needed for bone growth, which is why proper resistance training can help.

- Tension forces are experienced when molecules are pulled apart. Think about hanging from a pull-up bar, this causes the humerus and the supportive ligaments and tendons to experience tension, which is really good for strengthening tendons and ligaments.

- Shearing stress takes place when forces are traveling in opposite directions. (Think about being hit low and high at the same time in football causing the spine to experience a shearing force.) This type of stress leads to injuries.

- Bending loads happen when one side of an object experiences compression while the other side experiences tension. If an athlete has their foot planted while someone falls into the leg they have planted, one or more bones and/or joints will experience a bending load. This is another load that can lead to injury.

- Torsional loads happen when a part of the body experiences a twisting type of force. You can think about an athlete plating his or her foot into the ground to make a cut, and they rotate to turn. However, their foot stays planted in the ground causing a spiral fracture.

· Youth can increase strength significantly more with weight training versus normal growth and maturation.

· Plyometrics and explosive movements found in Olympic weightlifting induce improvements in Power.

· These improvements in strength and power are easily maintained with little continued effort but can continue to be enhanced with continued training.

· Improved Motor Performance Skills (Athleticism)

· Improved Resistance to Sports Related Injuries

· Improved Cardiovascular Risk Profile

· Help with Weight Management

· Enhanced Psychosocial Well-Being (relationships, mental health, etc)

· Improved Cognitive Performance (I will explain this a bit more later)

· Improved chances of maintaining a lifetime of health and fitness

Here are some videos that I have put out in the past if you want the quicker versions:

→So Weightlifting is Dangerous for Youth?

→Youth Resistance Training and Running Benefits and Risks

→ Resistance Training for Youth

Some updates to my stance-

I have been thinking about writing this revision to my stance on youth in regards to resistance training and the sport of Olympic weightlifting for quite some time. The holidays seemed to spark my ambition while being around my own children and relatives. Here are the topics that I will cover in this revision:

- Our Model in USA Weightlifting for Advancing Youth might be too Aggressive

- Using Velocity Based Training for Predictive 1RMs is a safe, effective, and timely alternative to testing true 1-Repetition Maximums, 3RMs, or 5RMs.

- A closer look at our Leadership Models with a focus on Process Driven Systems versus Performance Driven

- A closer look at how we as coaches are affecting our athletes mentally

- A more holistic approach is needed-

- Mindset and Sport Psychology

- Program Culture

- Nutrition

- Recovery

Our Model at USA Weightlifting and Other Sporting Organizations for Youth might be too Aggressive-

Image 1

Let me state this up front, I am not pointing my fingers at anybody. I am going to start this off by referencing what I have witnessed with the young athletes competing within USA Weightlifting, and then I will relate my observations to other sports. I found my way back to the sport of Olympic weightlifting around 2012, and by 2014 it consumed most of my time and energy.

From that time on, I was so excited at the amount of young talent the sport was attracting. For those reading this that are not Olympic weightlifting fans, youth athletes are those men and women ages 17-yrs-old and younger, and junior athletes are ages 18 to 20-yrs-old. Young men like CJ Cummings and Harrison Maurus led us to believe that our country was making real strides to becoming a force internationally for the first time in recent history. CJ and Harrison were winning youth and junior world championships and breaking world records. Both of them were competing at Senior World Championships while still youth and junior athletes. I mean it was crazy.

I had several conversations with fellow coaches in and out of USA Weightlifting about the rate of progression of both boys. One coach in particular that voiced concern was Coach Joe Kenn. At the time, I was uncertain. All I knew is that our 2020 Olympic Team was going to be filled with not only those two young men, but also two of the women were fresh out of their junior years: Jourdan Delacruz and Kate Vibert. That means half of the entire team was composed of these young folks that had been tearing it up during their youth and junior competitive years.

Based on that observation, I was a bit more aggressive with the training loads for my young athletes. At the time, I had several youth and junior Team USA athletes both men and women, and some of them were killing it just like CJ and Harrison. We were pushing the heavy loads and volume as well. There simply wasn’t enough data to make concrete decisions. There were International teams to qualify for, and I had athletes that wanted to qualify for those teams. Therefore, we pushed it and made those teams.

However, by the time the Olympics rolled around, CJ and Harrison hadn’t continued to develop quite like some of the other athletes around the world. I really don’t think it was the training load or volume, even though it probably played a part, but instead, I think it was more the pressure and constant need to perform that caused the damage. Especially during that quadrennial because the athletes qualified based on a points system requiring them to compete at a near maximum level at a high level of frequency.

Harrison did perform well, but not at the level he was constantly putting out in his younger years. However, by the time he competed in Tokyo, he was ready to be done with the sport and move on. It was the same for CJ. He struggled to keep his weight under control and didn’t peak well for the 2020 Olympics only making two of his six attempts, which led to a state of depression. You can read his interview on the International Weightlifting website here:

Imagine all the pressure that was on Harrison and CJ with everyone within USA Weightlifting looking to 16-yr-old boys to save the sport from its past lows. At 16-yrs-old I was playing three sports, hanging out with friends, and talking about the girls at school. Both of these young men are nothing but pleasant to be around. Unfortunately, they ended up being sacrificial lambs, so the rest of us could learn.

To summarize my anecdotal observations, I’m not sure that we should be pushing these young athletes to qualify for these competitions at all cost. I have seen athletes cutting weight to make youth and junior teams. I am not as concerned about the junior athletes, but I believe the youth athletes should focus on primarily having fun, learning proper technique, and slow rolling the gains. I witnessed the same issues within my own program.

Image 2

There was one young man (I have omitted his name) that was an incredible talent and still is. I remember Coach Don McCauley being worried about the rate of his progression telling me that we might be pushing him a bit too quickly. It wasn’t the load we were putting on him, but instead, it was the pressure that everyone was inadvertantly placing on him. By the time he was 13-yrs-old, people were comparing his performances to CJ and Harrison, which we were all excited about. At this point, it appeared that CJ and Harrison were killing it, and that they would have a long career dominating the sport.

Just like CJ and Harrison, I believe this pressure delayed his progression as an athlete. However, so far he has managed to maintain his love for the sport, and I believe that he will end up crushing it leading up to 2028. If he had continued to progress at a high rate, no doubt in my mind, he would be battling right now for 2024. However, now I am convinced that this slower progression will end up paying off.

My Thoughts on Progressing Youth based on my Anecdotal Evidence-

Whether you are coaching a weightlifter, baseball player, or football player, the focus should be on the athlete maintaining their love for the sport. I recommend letting them have fun while learning to master the fundamentals of the sport. They need to have friends, go on vacation, and focus on becoming a well-rounded human. I have watched too many coaches demand every ounce of the athlete’s attention to be placed on his or her sport. I believe this to be unhealthy and cruel, and not to mention, a detriment to long term development.

I have yet to hear a good reason for playing one sport all year before the age of 15-yrs-old. There is no proof that specializing in a sport before puberty will lead to any advantage for reaching elite status. However, the evidence is clear that this sort of specialization will increase the odds of sport related injury, increase psychological damage, and it leads to a higher rate of quitting the sport (Jayanthi N et al., 2013). Another thing I have noticed is that athletes participating in an individual sport having never participated in a team sport will lack certain leadership and social skills that come about naturally playing team sports. This is observation only, but it appears that sometimes they lack certain social skills like developing into leaders and participants that engage in a mutual, ongoing process of raising one another to higher levels of motivation, moral reasoning, and self-consciousness. They tend to focus on if others are aiding or detracting from their own experience and/or performance versus looking within on how they might be affecting others. I have also noticed a lesser ability for dealing with conflict. Lastly, I noticed a prevalence for blaming circumstances or others for poor performance versus owning the results and learning from those bad experiences.

Image 3

Until puberty, skill development and technique should be the coach’s focus. Proper movement should be observed at all times during this time period. Going heavy as in one-repetition maximums should be avoided, but progressing in this manner with a predetermined velocity using velocity-based training or using an Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale is advisable and safe. There should be very little room for compromising and unsafe movements like loading the spine during major amounts of flexion or knee valgus.

Yes, I am aware that mature Olympic weightlifters will sometimes display valgus to complete a heavy lift potentially producing a dynamic stretch shortening cycle calling on the adductor magnus for help with extending the hip. However, it’s still quite clear that massive amounts of knee valgus is a mechanism leading to knee pain, tendonitis, and ACL injuries. Social media is almost a curse encouraging coaches and athletes to attempt huge lifts to gain the attention of potential followers. You can’t get on social media without seeing a video of a 12-year-old girl or boy performing a clean or squat with their knees actually touching. If you want to review the literature, feel free to comb through the research I have referenced at the end of this article.

My recommendations:

- Avoid high degrees of knee valgus especially with preadolescent boys and girls

- Maintain a neutral spine (yes, I know that a neutral spine is a controversial term, but I am referring to avoid excessive amounts of flexion or extension in the thoracic and especially the lumbar and cervical spine)

- Use Velocity-Based Training if possible setting velocity limits for squats, pulls, and presses and establish velocity norms for cleans and snatches to avoid failure.

- Focus on technique and movement

- Avoid early sport specialization at least until after puberty

- Try to have off-seasons even if specializing

- Avoid overly high pressure on athletes until early adulthood 18+

- Make sure athletes are having fun at all ages and all times

- Your goal as a coach is for the athlete to leave you still in love with physical fitness and the sport

Using Velocity Based Training for Predictive 1RMs-

For years the debate over how to test the improvements with younger athletes has raged amongst the various experts. Some would say that 3-repetition maximums (3RMs) or 5-repetition maximums (5RMs) are safer than 1-repetition maximums (1RMs), but this makes very little sense. A 3RM or 5RM comes with the same amount of fatigue that a 1RM presents if not more. Therefore, neither option provides a safe option, but there is one that I have used now for nearly five years with great success.

With my young athletes and even my own children, I use velocity-based training (VBT) to test their absolute strength movements like the back squat, front squat, deadlift, or any press. The Olympic movements at this point in their development are missed due to technique, so I allow any breakdown in technique to decide the ending point. Remember, the force-velocity relationship in inversely proportional meaning as the mechanical load is increased, demanding more force that this increase in force will result in a decrease in velocity. That means as force is increased at any point on the velocity profile it will lead to an increase in the potential to produce force at all points.

Let me explain this in an even simpler way. In the back squat, 70% of one’s 1RM results in a velocity of 0.7m/s. If an athlete increases the amount that they are able to back squat at 0.7m/s, their ability to back squat at 0.3m/s (the terminal velocity for most athletes) increases as well. There is no need to actually test a true 1RM and risk a potential injury. We normally test the back squat at somewhere between 0.5 m/s and 0.6 m/s. This keeps them safe, but it tells me the information I desire. I only desire to know if there is improvement being met on the current program.

There is much more than absolute strength improvements to be tested with VBT. There are tests as well such as the Dynamic Strength Index, Reactive Strength Index, and Force-Velocity Profiles. I will briefly explain what each test reveals, and I will link to my articles on the GymAware website for you to dive deeper:

- Dynamic Strength Index (DSI) reveals how much of an athlete’s peak force capabilities are actually being used during more ballistic movements like a vertical leap.

- The DSI gives the coach an athlete direction as to focus on explosive movements, strength movements, or a combination.

- This test sheds light on whether or not the back squat equals improvements in ballistic movements like sprinting and jumping.

- Find out more with my article “Practical Uses for the Dynamic Strength Index”

- Reactive Strength Index (RSI) reveals an athlete’s elasticity and the efficiency of their stretch-shortening cycle (SSC) which are both directly related to an athlete’s sprinting, change of direction, and other ballistic movements.

- The RSI looks directly at an athlete’s drop jump from various heights.

- The relationship between the ground contact time and height of the jump clearly demonstrates the efficiency of an athlete’s SSC and elasticity at the ankle, knee, and hip which are all joints directly related to aforementioned athletic endeavors.

- Find out more about the RSI on the GymAware website: “Reactive Strength Index in Sports”

- Force-Velocity Profiles (FVPs) demonstrate the relationship between the two main components of power which are force and velocity. They also show:

- Where maximum power is demonstrated in regards to rate, which explains if the athlete is creating power at a rate that is related to the athletic movements required in their sport.

- FVPs also reveal at which quality of strength an athlete needs attention.

- Learn more about FVPs at : “Force Velocity Profile, the how, the why, and what to do with it”

A closer look at our Leadership Models with a focus on Process Driven Systems versus Performance Driven-

Image 4

While completing my studies at Lenoir-Rhyne University, I had the privilege of taking part in a Sport Psychology class. I approached that class with arrogance feeling that sport psychology was a subject lacking real science. I have never been so wrong. I have always considered myself a coach that taught with positive reinforcement. Yes, my words might very well have been positive, but I’m not sure about my facial expressions or the very things I placed importance upon.

Here’s what I learned. When dealing with athletes and especially youth, a process driven system will yield better results and leave the athlete with a healthy mindset. I made the mistake of focusing on performance for the majority of my early years of coaching. I would discuss only the end goal such as earning a scholarship or winning a championship. We would create competition within our walls placing great importance on winning the competition of the day. Such a focus causes athletes to place value only on the win or the end goal causing mental fatigue and even damage since winning every battle is impossible. Athletes will begin to place worth only on such victories creating an atmosphere of constant struggle. This is too much to ask of any athlete.

Yes, an athlete must have goals, but for every goal there is a process needed to obtain said goal. It’s the process that should be the focus of an athlete on a daily basis. Instead of approaching each training session with unreasonable arbitrary goals such as running a specific time or lifting a specific load, the literature points us to focus on the process of achieving these goals. An athlete can achieve a mental win each day focusing on a specific aspect of sprinting like the start position or the first pull of a clean. These are achievable leaving the athlete with a healthy mindset, which brings me to the next point.

A closer look at how we as coaches are affecting our athletes mentally-

I’m definitely not one of these coaches that believe in participation trophies because that’s not a good way of teaching habits applicable to the real world. However, at this point of my career as a coach, I am more concerned with how I am leaving athletes regarding their mental health and overall love for fitness than I am about them becoming my next champion. This is a big shift, and it’s a shift needed throughout the industry.

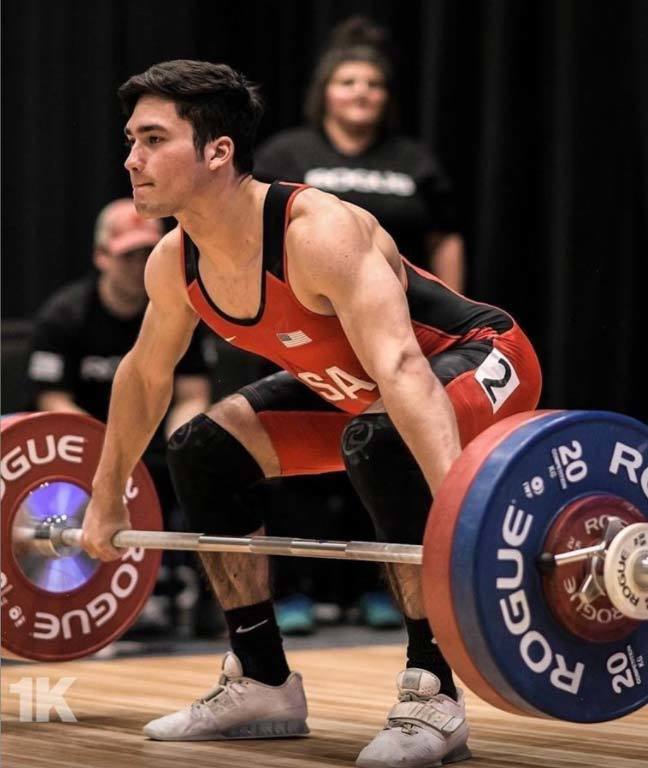

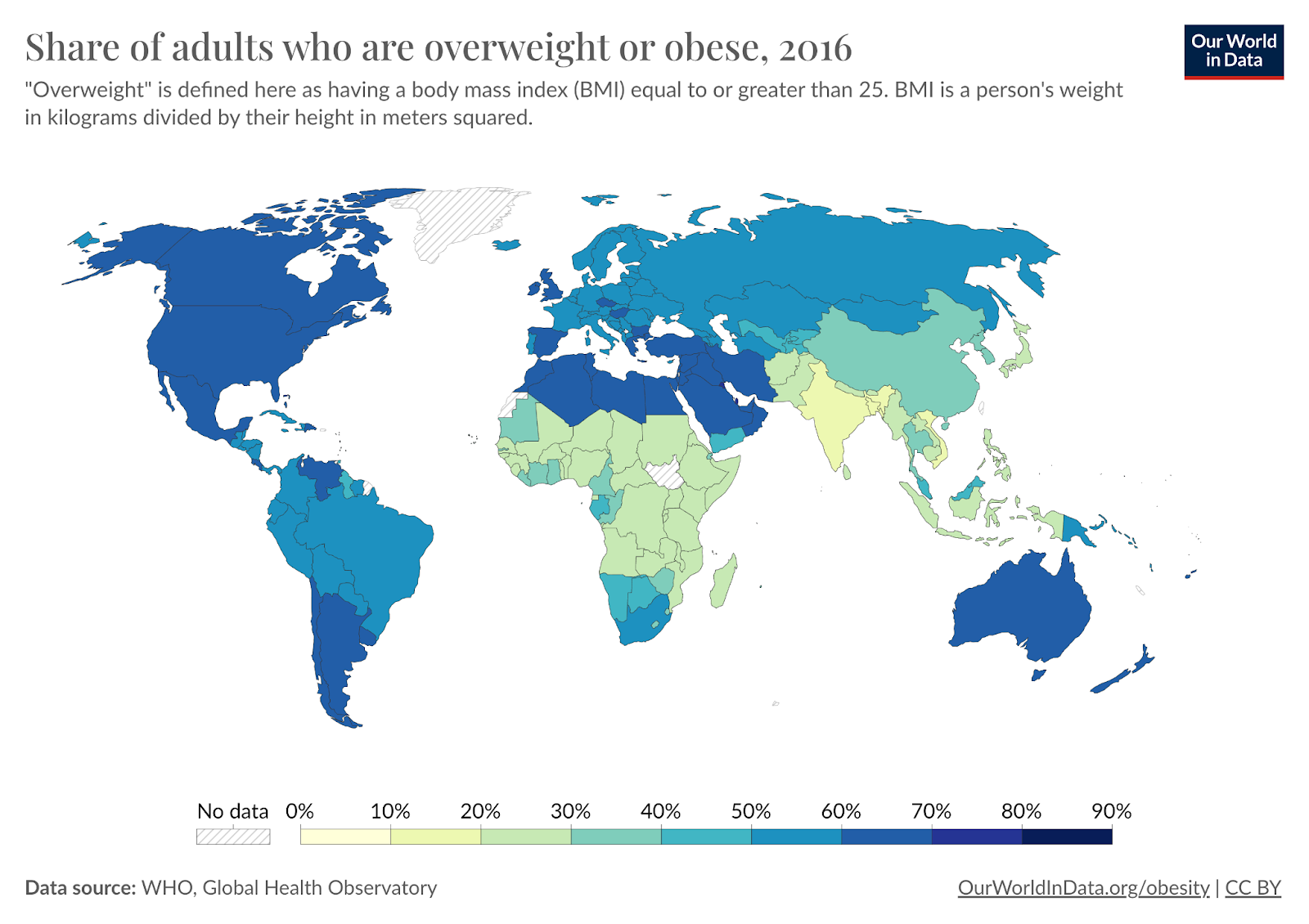

Obesity is on the rise in America and throughout the world. Are strength coaches partly to blame? It’s hard to measure, but I recommend taking a look at how your athletes are leaving you. Are they in love with working out? Did they have a mentally healthy experience? Odds are that if you spent the majority of the time focused on daily performance driven measures, a few of your athletes left you without sharing your love for training.

Image 1 below shows a bleak look at obesity in America and the world. Strength training is a great way to introduce a new lifestyle to overweight youth because they probably don’t love distance running. People love things that make them feel good about themselves. Strength training is a great way to increase activity levels for kids that otherwise might stay on the couch or in front of a screen.

If we can encourage our athletes regardless of their athletic ability, we can not only help them athletically, but maybe we can help direct them to a more healthy life. This is the real goal for me moving forwards. My mentor Coach Don McCauley was naturally gifted in this area. He didn’t care if you were the next Gold Medalist or just someone destined for the state championships. He was going to help you with every bit of his ability, and he loved every minute of it. This man continues mentoring me from the grave. Every year, I realize something else that he was trying to teach me.

Image 5

A More Holistic Approach is Needed-

The point of this entire article is to get across to all of the coaches in the world that we need a more holistic approach. We will talk programming and exercise selection until we are blue in the face. We will get fighting mad over whether or not the Olympic lifts should be used. However, deep down we all know that all of this is irrelevant unless we are teaching all of the aspects of physical fitness:

- Mindset and Sport Psychology

- Program Culture

- Nutrition

- Recovery

How are we helping our athletes regarding their mindset and mental health? I suggest getting a professional to help with this. There are two that I work with ongoing: Roger Kitchens and Gabrielle Villareal. Roger has helped me with a number of my athletes, and Gabrielle has been a major help with the way I parent. I admittedly need even more help in this area as I strive to be an even more positive influence in all the lives of my athletes. Mindset has always been an area that I feel secure in. It’s natural for me to help athletes shift their paradigms up from whatever they believe is possible. However, my ability to have a positive influence on each of my athletes regardless of ability needs improving. However, a coach has to take ownership in the areas they need improving. If they honestly believe that they have no area that needs some work, that’s a scary person with narcissistic tendencies. Personally, I would avoid sending my own children to a coach like that.

Program culture is an area that my good friend, Coach Spencer Arnold, excels above all other coaches. He takes the time to get input from each of his athletes, so that the culture is formed from the collective versus just him. This creates ownership which becomes much more likely to be adhered to. The problem is that time is required. This is the conundrum that we find ourselves in as coaches. The division of time between our athletes, our families, our health, and our faith. This conundrum has been the toughest equation for me to solve during these past three years. I’m still not sure of the answer, but I assure you that it is a concern that needs addressing.

Nutrition is a word that a lot of us throw around like a pinball. We will stay up until the late hours of the night working on our spreadsheets that contain our magical programs. Yet, most of us are aware that proper nutrition is the fuel needed to make our programs work. Without the adherence to a solid nutrition program, these magical programs that we debate to the point of arguing online for the world to see are worthless without the correct fuel. If you want your athletes to battle through high volume programs, they need the calories to do so. They need carbs for fuel, protein for muscle, and fat for energy and hormones. This is one area that I am in the process of handling for my athletes with my friends at Rapid Health. We are going to personalize macronutrients and micronutrients. It was Dr. Andy Galpin that said macronutrients are for the way we look while micronutrients are for the way we feel.

Recovery is another element of athletic performance that is necessary to maximize the results of our athletes. This starts with sleep. I laugh when my athletes ask about ice baths and saunas when I know that they are only getting 4-5 hours of sleep per night. One of the things that I have discovered while testing athletes at Rise Indoor Sports is that hardly any of them are getting proper sleep. 99.9% of them are on their cell phones until they finally drift off to sleep. We know by now that this blue light exposure is interfering with melatonin release and in turn sleep quality. We need recovery and nutrition protocols to match our programs. This is what we should be talking about online.

Summary-

Yes, athletic performance has advanced in the last decade, but one thing is for sure and that’s we still have work to do. We need qualified coaches working with our youth. Those coaches need to focus on the quality of movement versus the load on the bar at least until after puberty. Even more importantly, the effect we have on our athletes needs to be a positive one. Our athletes should leave us in love with training and with a better understanding of themselves. They should leave us with a positive outlook on the experience as a whole.

We should get together in regards to taking systematic approaches towards our athletes’ mental wellbeing, the culture of our programs, the nutrition approaches of our athletes, and their recovery systems. The days of arguing like children about our program spreadsheets should be over. The mental, physical, and spiritual health of our athletes should be the primary concern. This article isn’t pointing a finger at an individual or some team. This article is in regards to our profession as a whole. We need to do better. We have to do better.

Sincerely,

Coach Travis Mash

USAW Senior International Coach

New References:

- Bell, David & Vesci, Brian & Distefano, Lindsay & Guskiewicz, Kevin & Hirth, Christopher & Padua, Darin. (2012). Mus cle Activity and Flexibility in Individuals With Medial Knee Displacement During the Overhead Squat. Athletic Training & Sports Health Care. 4. 117-125. 10.3928/19425864-20110817-03.

- Wilczyński B, Zorena K, Ślęzak D. Dynamic Knee Valgus in Single-Leg Movement Tasks. Potentially Modifiable Factors and Exercise Training Options. A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(21):8208. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17218208

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical Measures of Neuromuscular Control and Valgus Loading of the Knee Predict Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes: A Prospective Study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;33(4):492-501. doi:10.1177/0363546504269591

- https://barbend.com/knee-valgus/

- Jayanthi N, Pinkham C, Dugas L, Patrick B, Labella C. Sports specialization in young athletes: evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health. 2013 May;5(3):251-7. doi: 10.1177/1941738112464626. PMID: 24427397; PMCID: PMC3658407.

- Hallé Petiot G, Aquino R, da Silva DC, Barreira DV, Raab M. Contrasting Learning Psychology Theories Applied to the Teaching-Learning-Training Process of Tactics in Soccer. Front Psychol. 2021 May 4;12:637085. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.637085. PMID: 34017282; PMCID: PMC8129189.