Ever since I posted the video on Twitter of the young athlete performing a clean with terrible technique, I feel that most of my attention has been drawn to the high school strength coaching world.

But this article is about all coaches in the strength world: high school, collegiate, CrossFit, weightlifting, powerlifting, etc.

I want to teach these coaches how to stay off the CCR… the crappy coaching radar.

A lot of coaches possess all the skills necessary to stay off of the CCR, but they swerve out of their lanes. Suddenly they are directly in the bullseye of the CCR.

Here’s how to stay out of CCR trouble.

1. DON’T TEACH WHAT YOU DON’T KNOW

Look, no one loves Olympic weightlifting more than me. But just because you go to a Saturday clinic and someone tells you that Olympic weightlifting is a great way to get athletes ready for their sport doesn’t mean that you start teaching the snatch and clean and jerk come Monday. You have to know how to teach the lifts. Personally I think teaching the snatch and clean and jerk isn’t that hard, but that’s because I have years and years of experience.

If you are really good at teaching the squat, press, and deadlift, I suggest sticking to those movements. Most athletes are so raw that anything will prove to be monumental in their development. Whatever you teach, you need to be 100% proficient in teaching that movement.

Athletes will benefit in a big way from squats, benches, and deadlifts with a few simple plyometrics and accessory movements thrown in. However, poorly taught cleans and snatches will not only yield poor results, but now you have put your athletes in danger. I’m sure that’s the opposite plan that most coaches intended, but those are the results nonetheless. I suggest getting really good at two to three movements first, and then slowly add one or two movements to your toolbox each year.

[thrive_leads id=’11558′]

2. ADDING POINTLESS ACTIVITIES TO A WORKOUT JUST TO MAKE IT “HARDER”

You see this all the time. Old school coaches love to teach athletes how to work hard, and I agree that good old-fashioned hard work is something everyone needs to learn. But whatever you do, it needs to be done safely.

Some coaches see a program with 5 x 5 at 75% on the back squat. Then they think if 5 x 5 at 75% is good, then 10 x 5 must be better. You know… because if our rival high school is doing 5 x 5, then we will work harder than them with 10 x 5. Sounds awesome! Right?

Wrong! Now you’ve placed the volume into a dangerous level.

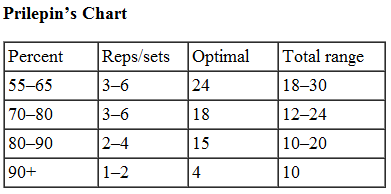

A good place for coaches to reference regarding volume is Prilepin’s Chart:

As long as you stick to these parameters, you will be pretty safe. Based on this chart, 50 repetitions at 75% intensity would obviously be more than double the maximum suggested volume. This chart was produced back in 1974 after looking through the numbers of hundreds of top-level athletes in the old Soviet Union. It has stood the test of time, so you can trust it as a great foundation.

3. FAILING TO EXPLAIN THE WHY

Coaches really need to be able to answer the why to whatever you are prescribing. This one rule will keep you out of trouble. If you don’t know the why to your program and every exercise prescribed within the program, stop reading this and go figure that out. If I can’t explain why a movement is in a program, I drop it.

If you find yourself getting mad or offended when athletes ask you questions about your program, that’s probably a sign you are feeling insecure about your program. If this is you, change things right now. You should invite kids to ask. There is no better time to explain the benefits, connect with your athletes, and to get the buy-in that we are all looking for.

Connecting with your athletes and getting buy-in is more important than your program itself. If you can connect with your athletes, you can create real change within their lives. If an athlete believes that something will work, it will work. If they don’t, it won’t. That’s just a fact.

One last point about this issue is that within time constraints placed on you in the school system, none of us have time for an exercise that is of no value. This is another reason to know your why for each and every exercise.

4. PRESCRIBING WORKOUTS THAT DON’T FIT THE CLASS SIZE OR AVAILABLE EQUIPMENT

Before you design any workout, you need to ask yourself a few basic questions:

- How many people will I be coaching per class?

- What equipment do I have readily available?

- How much time do I have per class?

- What is the main goal I am hoping to accomplish?

A version of Coach Joe Kenn’s Tier System would work nicely here. For example you could front squat, box jump, and plank for the first set of exercises. Then you could finish up with lunges, lateral step-ups, and a carry for the next set and be done. This would take forty to fifty minutes at the most.

What happens if a few people aren’t ready for the front squat? That’s easy. You group those folks together, and they’re doing kettlebell goblet squats, box jumps, and a plank. You have to know your area and your athletes.

5. WRITING A PROGRAM ON THE BOARD AND THINKING THAT IS COACHING

This is my biggest pet peeve and the number one mistake I hope to change. We’ve all seen a high school coach write a workout of the day on the board, explain it a bit, and then walk out of the room until the end of class.

If this is you, you need to change things right now. You are putting your students at risk. You are putting their very lives at risk. You and the school need to be held liable.

Do I sound upset? If so, well… I am. I have children, and I want them to be as safe as possible when they are away from me. I need to be able to trust the adults that are supposedly teaching them at school. If you don’t want to do the job, then don’t. You should quit if you don’t want to do it. If you are in a public school just collecting a check, you need to reevaluate your priorities. You might not like your students, but they are someone’s children.

Real coaching means you are coaching every repetition of every set. Don’t tell me your athletes lift perfectly. I have the best weightlifters in the country, and they still need direction each and every day. Don’t tell me that your 16-year-old boy is performing a clean perfectly on every repetition. Heck – when they perform a repetition perfectly, that’s the perfect time to coach them. That’s when you tell them to remember exactly what they just did, so they can repeat it.

If you want your athletes to improve and more importantly to be safe, you have to be present. I’m not just talking about being in the room. I’ve watched coaches prop their feet up on a desk and read a magazine. I am talking about being attentive to what’s going on.

6. CHASING NUMBERS AT ALL COSTS

This is one of the most common mistakes. Coaches get so caught up in big numbers that they let movement go right out the door. You will see bench presses bouncing off the chest, high squats, and crazy cleans like I posted a few days ago. Why? For what? Just so the coach can tell their friends and athletic directors that their guys are getting strong. It’s crap, man! Learn to coach so you can actually get someone strong in a way that will translate to them being a better athlete. The best way to do that is focus on perfect movement.

If I take a guy with less than perfect movement and improve his movement significantly, I have made him a better athlete whether I got them stronger or not. On the other hand, if their squat goes up while movement quality goes down – congratulations, you just created a worse athlete. This is why I am excited about creating some basic standards for movements and teaching these standards to coaches all over the country. I want to emphasize functional movement patterns over increases in strength. Sound crazy coming from a strength guy? It shouldn’t because a functional movement will always be the strongest movement.

[thrive_leads id=’11559′]

7. GETTING TOO COMPLICATED

Keep it simple! There is no reason to get fancy, guys. If you’re getting results from basic movements and programming, then keep it basic. Here’s another rule that will never steer you wrong: Get the most out of the least!

If you are getting results from a basic barbell squat, there is no reason to add bands or chains. If linear periodization is getting the job done, then don’t worry about conjugate. Keep it simple and get the most out of the least.

This is a lesson I learned a few years ago. I swear there is a paradigm shift that all strength coaches go through. We start out keeping it simple, focusing on good movement, and getting a bit stronger. Then we start reading all these fancy books and articles. The next thing you know our programs look like something you might find on an engineer’s desk at N.A.S.A.

Then someone (such as Coach Kenn or Coach Dan John) reminds us to slow our rolls and keep it simple. Then we start simplifying things, and we realize that results come much quicker with a simpler approach. This goes for all levels – not just high school.

The simplest workout I ever wrote brought the most gains. I wrote a basic four-days-per-week workout with high frequency and high intensity for Cade Carney to get ready for his freshman year at Wake Forest University.

Here’s an example of what it looked like:

Day 1

Back Squat (with belt) – 1RM (paused 2 sec), then -15% for 2 x 3 (not paused)

superset with 36″ Box Depth Jumps and Touch for Height – 3 x 5

Clean EMOMs – Start at 70% for 8 x 1 rep, working up heavy

Bench Press – 1RM (paused 2 sec), then -15% for 2 x 3 not paused (last set is 3+)

Dips – 3 x submaximal reps

superset with KB Bat Wing Rows – 4 x 8

Day 2

Front Squat (with belt) – 1RM (paused 7 sec at a 8 RPE)

Complex: High Hang Clean + Low Hang Clean – 1RM (8 RPE)

Push Presses – 1RM, then -15% for 2 x 3 (last set is 3+)

Glute Ham Raises (eccentric slower than concentric) – 4 x 6 weighted

KB Staggered (one OH and one to the side) Carries – 4 x 20 yd each way

Day 3

OH Squat – 1RM (2 sec pause in bottom), then -15% for 3

Complex: Clean Pull + Clean – 1RM

Bench Press (pause all reps, add mini bands) – 8 x 3, start at 40% + bands, working up heavy but no misses

Deadlift Max Effort – 1RM from 4″ deficit

Chest to Bar Pullups – 3 x submaximal reps

superset with KB Swings – 3 x 12 reps

Day 4

Warm Up with OH Squat Variations – work up to 70% for 3 reps with 1st rep paused 5 sec

Front Squat (with belt) – 2RM

Hang Snatch – 3RM

Strict Presses – 1RM, then -15% for 3

See how simple it was? We used lots of repetition maximums because he was fresh out of football season. We agreed to stop one or two sets before potential failure unless I gave him the green light.

This simple program worked like a charm. His squat went up by over 70 pounds, bench press by over 50 pounds, and clean by over 70 pounds. Sounds crazy I know, but he was weak when he first started after a long season of football. His team actually won the state playoffs, so he was really beat down. Needless to say, he made a huge impact at Wake Forest to the point that all of his coaches have been by our gym to check us out. As a strength coach, there is no bigger compliment than to send a guy or gal to college only to have their new strength coach commend your work.

MY COMMITMENT

I am committed to making the weight room in high schools all across America a safer and more productive place for student athletes. You might think that I am crazy, but there is an army of us preparing for this battle. It’s not just me. I am developing a database of folks who want to help out. I just spent an hour talking with Coach Sean Waxman last night, and he’s fired up as well. If you get the two of us loudmouths together, things will change just to shut us up.

[thrive_leads id=’11558′]