Thanks to the efforts of strength coaches such as Alex Viada, Travis Mash, and Brandon Lilly, we’re seeing a shift in the strength sports community.

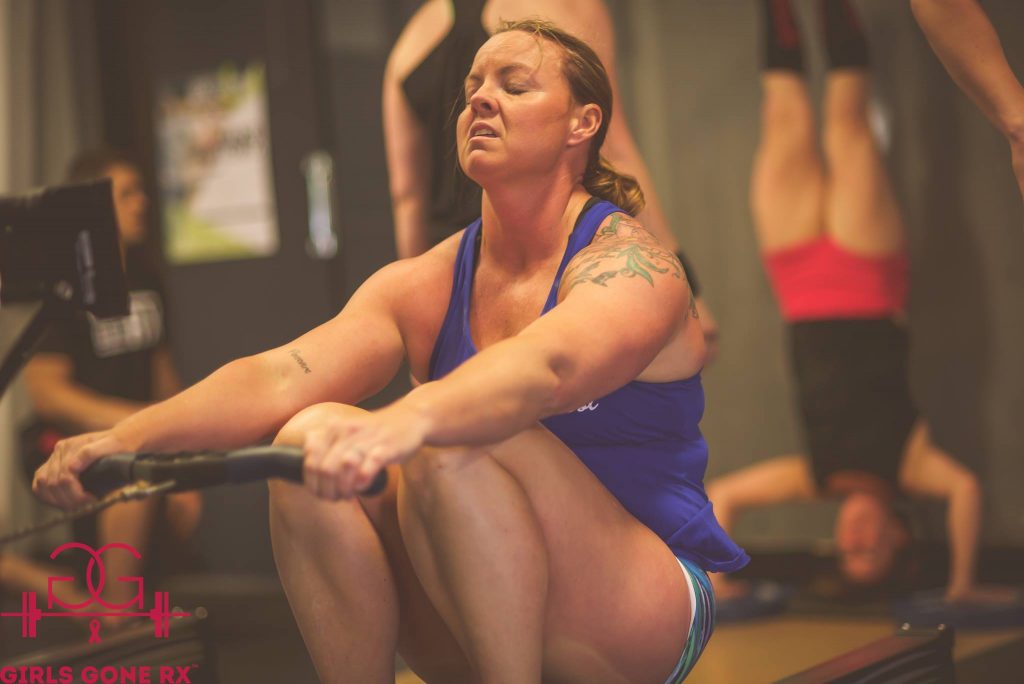

We’ve moved from the stereotypical “fat guy with a big gut who eats three Big Macs every meal” to a leaner, fitter, healthier strength athlete. As someone who used to work in cardiac rehab and helped start two programs, this warms my heart (no pun intended).

But it also concerns me because cardiovascular exercise, especially in bigger people with various health issues, needs to be done safely in order to minimize risk. Risk can never be eliminated, but it can be minimized.

[thrive_leads id=’9790′]

So let’s go over some heart health advice for the strength athlete. Disclaimer: I’m not a doctor – nor did I stay at a Holiday Inn Express last night, so it’s tough for me to give very specific pieces of advice without understanding your situation and your goals. Take what I say with a grain of salt.

Here are the two most important pieces of advice for strength athletes who want to start taking care of their cardiovascular health.

Get a blood test

People ask me all the time – what supplements should I take? My answer is… get a blood test. I don’t know what nutrients and hormones you have deficiencies or excesses of. A blood test can help reveal all that.

This gives you a good start in terms of dietary changes and/or supplementation if needed. By contrast, overdosing on multivitamins may give you excess levels of fat soluble vitamins and/or just lead to you having really expensive urine from the vitamins that you pee out.

Get a graded exercise test

While there are various protocols for how these are done, a graded exercise test involves exercising on a stationary bike or treadmill at a gradually increasing resistance and/or speed. During these tests the evaluator will measure your ECG (heart rhythm), blood pressure, (if present) chest pain, and heart rate along the way to determine a safe cardiovascular exercise intensity range. This is the range that will enable you to improve your fitness while not working into an intensity that provokes symptoms in an unsafe manner.

When I worked in cardiac rehab, this method minimized the amount of incidents to one episode of chest pain over many years. Conversely I’ve heard of other centers that don’t give patients specific exercise intensities, and they report high rates of chest pain and even heart attacks during sessions. You don’t want that happening to you.

Also getting these tests (and just ECGs) done in general can help detect heart defects, such as the one that killed 2005 World’s Strongest Man runner-up Jesse Marunde.

Seek out a cardiologist or go to an ACSM (in the US) or CSEP (in Canada) Certified Exercise Physiologist. Make sure your practitioner has performed these tests before.

With these tests out of the way, now we move on to building our heart health with the following concepts.

1. Start with low impact exercise

While prowler pushes and hill sprints are quite popular, many athletes may not have the cardiovascular fitness or the orthopedic health to do them without developing pain, aggravating pre-existing issues, or just plain getting exhausted and throwing up. Plus if you’re a strong athlete, these methods are harder to recover from and should be used more sparingly.

By contrast I’m more of a fan of low-impact options:

- Sled pulls

- Sled walks (props to Jim Wendler for this idea)

- Stationary bike or recumbent bike

- Incline treadmill or weight vest walking

What about running?

Running is a higher stress activity that can have injury rates actually higher than those of strength sports. That’s not to say you should never run, but the decision to run has to be looked at in terms of the following criteria:

- What is your general health like? If you have cardiovascular, pulmonary, or lower body orthopedic issues (like joint or muscle pain), then running may not be the best choice for you.

- What is your baseline fitness like?

- What are your goals? Do you plan to run or are you just using it as a general means of getting in better shape?

2. Prepare

Make sure to do your cardio in areas that have people with appropriate first aid/AED training in the event that something does happen.

3. Start Easy

When in doubt, start easy. One thing I learned from my experiences in ICU and in pulmonary rehab is that a little bit of cardiovascular fitness can go a long way in terms of improving health, disease prevention, and improving recovery from hard training.

Athletes with a Type A mindset can often (in my opinion) go way too hard on their cardio and end up puking, passing out, or just plain stalling their recovery from training.

Once you’ve had your stress test and know what exercise intensity is safe for you, I recommend starting at a lower volume and intensity.

4. Build volume before building intensity

A common saying I’ve heard is to build anaerobic power before anaerobic capacity and to build aerobic capacity before aerobic power. None could be truer.

In simple terms, focus on building endurance to 20-40 minutes per session within your desired range before adding intensity.

If you’ve built a good base of cardiovascular fitness and are cleared to exercise at a higher intensity through a graded exercise test, then you can progress to more strenuous methods.

Just because you’re a strength athlete doesn’t mean you have to be a 300-pound cardiac patient during or after your career. Take these steps to heart and let me know how things turn out.

Pingback: Why Strength Athletes Should Condition by Crystal McCullough – Mash Elite Performance

Pingback: A Guide to Starting Running for the Strength Athlete – Mash Elite Performance